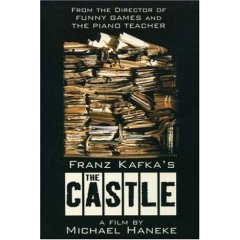

| The Castle. F.Kafka - Dir.Michael Haneke |

|

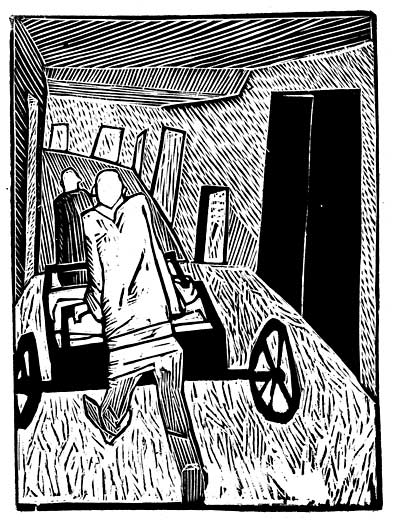

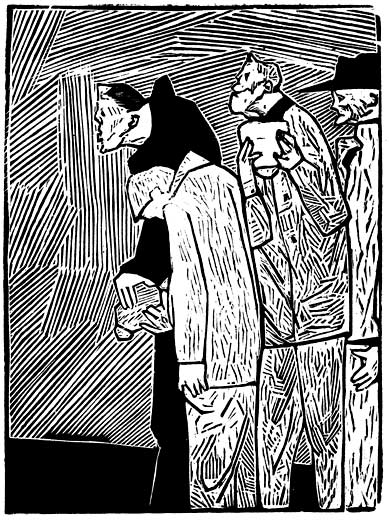

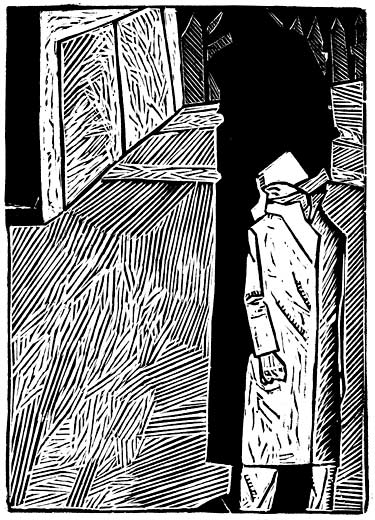

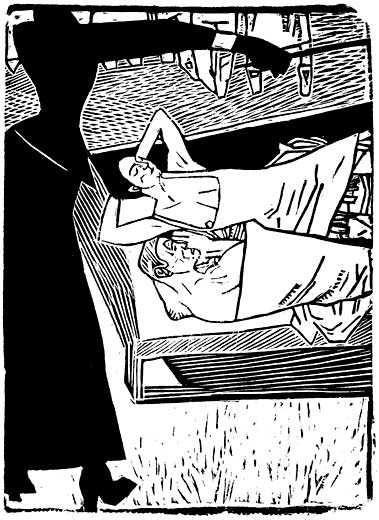

Illustrations for Kafka''s The Castle - Olga Kazakova |

Kafka''s The Castle - Olga Kazakova |

Kafka''s The Castle - Olga Kazakova |

|

Kafka''s The Castle - Olga Kazakova |

Kafka''s The Castle - Olga Kazakova |

|

|

view from the Castle |

The Royal Route to the Castle (Kafka was Prague and Prague was Kafka) |

Golden Lane is a very little street with nice little houses. Frantz Kafka lived in house No. 22 from 1916 to 1917 |

|

|

Franz Kafka''s grave in Prague |

Trail - Leszek Zebrowski |

|

The Castle - Wiktor Sadowski |

The Castle - Stasys Eidrigevicius |

Franciszek Starowieyski |

|

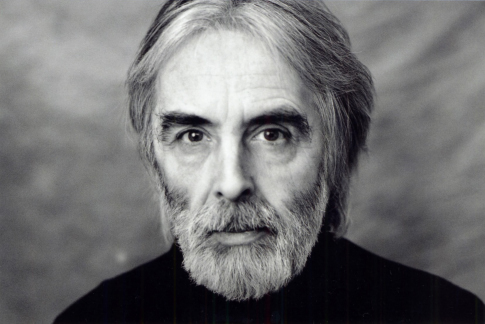

Michael Haneke |

The Winter Wanderers |

Michael Haneke |

|

|

|

|

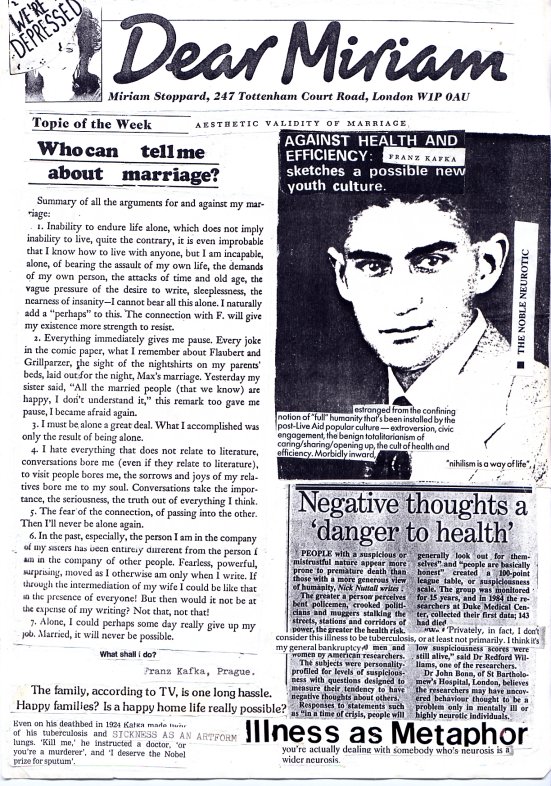

The Castle is a scathing take on bureaucratic entrapment, adapted faithfully from Franz Kafka''sfamously unfinished novel. K, a land surveyr, is summoned to work at the castle and its surrounding village by a mysterious count. When K arrives, he finds the hostile and incompetent villagers blocking his accass to the castle at every step. Fans of the director''s experimental studios will appreciate this impressive foray into surrealism, while literary types consider Haneke''s spectral adaptation the most faithful to Kafka yet committed to film. 1997, Austrian Film Archives.Dir.Michael Haneke

"And yet Kafka was Prague and Prague was Kafka. Never had it been Prague so perfectly, so typically, as during Kafka''s lifetime, and never would it be so again. And we, his friends, ''the happy few''...we knew that the smallest elements of this Prague were distilled everywhere in Kafka''s work."

(Johannes Urzidil in The World of Franz Kafka.)

My first visit to Prague was in 1963, when the city was sequestered behind what Winston Churchill had defined as the Iron Curtain. The Gothic spires and Baroque domes that give the skyline its fairyland aura were masked with a brown haze of industrial pollution; grim-faced men in Marxist gray raincoats stalked through the streets. Did I imagine the shade of Franz Kafka lurking at every corner?

For most of his life, Prague had been the third center, behind Vienna and Budapest, of the Hapsburg''s Austro-Hungarian Empire. In its golden age, centuries ago, the city was capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia.

When I returned in the last year of the 20th century, exactly one decade after "the Velvet Revolution" of 1989, Prague had become the capital of a new Czech Republic, thrashing about in a joyful chaos of capitalist free-thinking. Suddenly the claims of more optimistic Kafka contemporaries like Hans Kohn, the historian of nationalism, were once again credible.

"Prague is one of the most beautiful cities in Europe," Kohn asserted in his memoir Living in a World Revolution: My Encounters with History. Recalling his youth before World War I, he declared that the Moldau River (the Vltava since German names were changed to Czech) was "more intimately a part of this lovely capital than is the Danube in Vienna, the Tiber in Rome, or the Thames in London." Moreover, the views it affords are lovelier than the Seine''s in Paris, at least in his view.

(A Literary Walking Tour

By Marylin Bender).

Small houses along the castle wall were once occupied by guards, and then for a time poor artists like Franz Kafka, and finally, as with all things, tourist shops. Im sure that when the world comes to an end, the tourist shops will survive.

Franz Kafka''s Prague 1

This view of Pragueбкlooking down from the Castle near Hradз┌any Squareбкlooks as if it could be from Kafka''s time. He rented a small house at Golden Lane 22 (Zlatз╥ uliз┌ka 22) near here, where he used to get the peace and quiet he needed for his writing. It was just one of many places where the German-speaking author lived in Prague.

In 1972, well before he started writing outside of the academia, W. G. Sebald wrote a great essay called б░The Death Motif in Kafkaбпs The Castle.б▒ In the essay, Sebald mentions the particular Adorno quote cited above to link Schubertбпs winter wanderer to Kafkaбпs K, to emphasize the point that the image of journey or an aleatory hike is the symbol of death in both Schubert and Kafkaбпs works. It should also seem obvious that Sebaldбпs own prose works operate on this principle as well. Writing about Kбпs yearning for death as a desire for salvation, Sebald writes that in death, K can avoid the terrifying alternative - to be a б░stranger and pilgrimб▒ on earth, unable to die like Kafkaбпs Hunter Gracchus, or the б░Wandering Jew.б▒- http://selfdivider.com/base/?p=214

Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke is among the most celebrated and controversial figures in the world of contemporary world cinema. His films have been divisive and disturbing affairs that leaves audiences shaken and uncertain. He holds up a mirror to a world of extreme anxiety, offensive violence and a lack of human empathy. He has inspired amazing performances from his actors, leading many to win international awards. His cinema is ferocious, compelling and unforgettable.

Haneke''s films, told with exquisite precision and in riveting detail, shock audiences out of their indifference to the suffering of others and challenge their unquestioning acceptance of perceived reality. His themes center on alienation and social collapse, the fetishing of violence and the nature of individual responsibility and collective guilt. His tacit refusal to provide falsely comforting Hollywood endings has given him cinema a reputation as "rough going" and pessimistic. However, those prepared to look into the abyss of his chaotic world will find, among other things, the potential for hope and redemption and the whisper of a perhaps better outcome for the future.....if only the hard lessons can be learned and absorbed.

Haneke is, perhaps, the most controversial of contemporary European directors. His films, all of which are determinedly successful in making no concessions to the viewer, have both been alienated audiences (being booed at Cannes) and won them over (including a 33-week theatrical run in the US for his most recent title released there), and he has established a position as one of cinema''s important provocateurs, a concept lost in an era where cultural/political subversion is often seen as passиж, or conceived with jaundiced, anti-humanist cynicism. Equally importantly, he has presented demanding philosophical questions in a formal cinematic language that has a bold and uncomprising nature to match its content.

Born in 1942, Haneke entered film-making rather late in his career, after distinguished work in Austrian theater complemented by seriously engaged, ongoing study of philosophy and psychology. His first feature, Der siebente Kontinent (The Seventh Continent, 1989), is a staggering work based on a news story about a family opting for collective suicide rather than continuing in the present alienated world. Unable to accept the notion that the family took their own lives (could the terrors of daily life override the life instinct?), relatives insisted that authorities pursue the case as a murder, despite all the evidence militating against such a conclusion.

WiKi about M.Haneke - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Haneke

M. Haneke has examined, in a startling variety of forms and mediums, the most essential questions of modern existence- how are the repercussions of our actions amplified and transformed by the c

society we inhabit/ How do our emotional crises reflect the political turmoil we often try to dene? Often posing these questions in political pointed, formally challenging terms, Michael Haneke has consistently proven the sustained urgency and relevance of cinema, picking up a great number of supporters (and detractors) in the process.

Michael Haneke

Adorno -Schubert-Kafka

Polish Poster Gallery

Photo Gallery: Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

FRANZ KAFKA''S PRAGUE