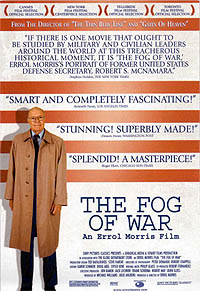

| The Fog of War - Errol Morris'' Political Documentary 2003 |

|

|

|

Errol Morris http://www.icommag.com/march-2004/march-page-1c.html - new project about artistic freedom |

|

|

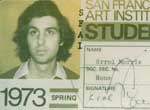

Errol Morris 1973 |

http://www.movienet.com/fogofwar.html - 13 Questions and Answers |

It is beyond the human mind to comprehend all the variables, says Robert McNamara of the complicated business of waging war. The 85 year-old former US Secretary of Defense is talking to director Errol Morris about his behind-the-scenes involvement in some of the 20th century''s most significant events: World War II, the Cuban missile crisis, Vietnam. Do his reflections make good sense, pointing to the need for political leaders to be wary of the consequences of their decisions? Or is he hiding from the truth about his past, a war criminal in the business of fabricating an apologia for his actions?

In The Fog of War (Errol Morris, 2003), McNamara expounds at length about his Zelig-like life: his recall, from the age of two, of the celebrations in the street at the end of World War I; his university years at Berkeley; the beginnings of an academic career at Harvard; his time in the air force in the Statistical Control Office under General Curtis LeMay during World War II; his work as the director of the Ford Motor Company. He also looks back on his time as an advisor to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations; the effect of his political career on his family; and his departure from government after privately expressing dissent to LBJ about US involvement in Vietnam. His subsequent career, as president of the World Bank (1968-1981), is mentioned only in passing.

Taking its lead from McNamara''s 1995 book, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, Morris has arranged his film around 11 lessons, adding a prologue and an epilogue. He also deploys a veritable battery of archival material both to support McNamara''s reflections and to comment upon them

Much of the negative reaction to the film has come from those concerned by what they perceive to be a lack of intervention on Morris'' part, charging him with allowing McNamara a platform from which to speak, relatively unchallenged. For his part, Morris has insisted in interviews on his ambivalence about his subject, but he shouldn''t have had to. Even aside from some of the extraordinarily revealing confessions he''s been able to extract from the man, it''s clear in the film.

The prologue provides a strong indication of what''s to come. It begins with old black-and-white off-cuts from a press conference in which McNamara is presenting himself as a man eager to be accommodating, long before the cameras are supposed to be rolling. Do you want it lowered? he asks about a map he''s about to use. Let me ask the TV first: are you ready? He''s being helpful, but it''s also a performance designed to establish the terms of the relationship between a public official and his interrogators. He''s got the first shot in, and nobody''s even noticed.

It''s not by chance, then, that the next sequence is some generic footage set aboard a battleship. The crew on board are readying for combat, Morris drawing an analogy between them and what McNamara is doing. And when the consummate politician then tries to use the same trick on Morris asking him if the voice levels are right Morris is ready for him, aggressively shouting back that they are.

When McNamara later talks about Vietnam, Morris inserts images of dominoes falling across a map of South-East Asia, in reference to the so-called domino theory, now discredited, which had countries falling one after another, in sequence, to the perceived Communist monolith. But then, when McNamara subsequently refers to the ways in which mind-sets themselves launch chains of events, Morris repeats the same images by way of directing attention to McNamara''s and at least three US administrations'' own mind-sets at the time. So much for a lack of intervention. And so much for the way that, according to J. Hoberman in a remarkably ill-informed reading of the film in the April 2004 issue of Sight and Sound, Morris'' feelings are nowhere apparent in the film, and for the way he allows McNamara to put his own spin on the Vietnam War (p. 21).

The Fog of War is only the second time that Morris has dealt with a public figure (the first was physicist Stephen Hawking in 1991''s A Brief History of Time). The rest of his work (including films such as The Thin Blue Line [1988] and Mr. Death [1999] and the 17-part TV series, First Person [2000, 2001]) has been about people who live far from the spotlight. The one thing they all have in common is the way they create private worlds that they can feel safe in, that they can control. Morris shows that McNamara is no exception.

The preceding is a revised version of my review of The Fog of War published in The Sunday Age on March 21, 2004. The following is the transcript of a video-link interview arranged by Columbia Tri-Star''s Cheryl Mulholland and recorded before a public audience at Melbourne''s Nova cinema in March 2004.

Tom Ryan

Making History:Errol Morris, Robert McNamara, and The Fog of War

Oscar Photo Gallery

Errol Morris: Breaking Through the Fog of War

Peace of mind

http://www.errolmorris.com/