| International Film: Akira Kurosava''s Rashomon (1950) and others |

|

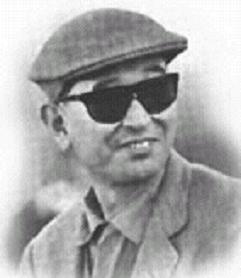

Akira Kurosava |

Rashomon |

Rashomon |

|

The Spiritual medium tells the murdered husband''s version |

|

The fierce and evil bandit |

|

Kagemusha (The Shadow Warrior), 1980 |

Ran, 1985 |

Dreams 1990 |

In ancient Japan, a woman is raped and her husband killed. The film gives us four viewpoints of the incident - one for each defendant - each revealing a little more detail. Which version, if any, is the real truth about what happened ?

The basic tale is this: a woman and her husband, a Samurai, are travelling through a forest when they meet a bandit. The bandit has sex with the woman and the Samurai ends up dead. That''s it. This tale is related to us through the woodcutter and a monk who saw the protagonists give their evidence to the police (the dead Samurai through a medium), but unfortunately the three tales conflict with one another. Each confessor says that they killed the Samurai, and then we hear from the woodcutter who in fact witnessed the event, who gives us a version of events that borrows from each individual account, and is still less credible!

The conclusion presented by Kurosawa seems to be firstly that individuals see things from different perspectives, but secondly, and most importantly, that there is no objective truth. There is no answer as to what took place in the forest, and Kurosawa offers us no way of knowing what went on. Each story is as credible as the other, and so no conclusion about guilt can be reached. We even have to think at the end that as the whole thing is reported to us by the woodcutter and priest, was there any truth in anything we heard at all?

This film leads to an especially tricky conclusion for a movie-goer! Your eyes are supposed to show you objective truth, but they don''t. The camera is supposed not to lie, but it does.

In medieval Japan, four people have different versions of a violent incident when a bandit attacks a nobleman in the forest. Indescribably vivid in itself, and genuinely strange (one of the versions is told by a ghost).

In one sense, RASHOMON does present a kind of intellectual puzzle. Perhaps because the clues to the puzzle are singularly cinematic, it''s solution did not appear obvious. The notion that the film was about the complete relativity of truth, i.e., that there is no truth, appeared in early English language reviews of the film. It has now achieved the status of a kind of conventional wisdom, e.g., even some people who have not seen the film will say, upon hearing the name RASHOMON, something like, "Oh! You mean the film about the relativity of truth"...

The film contains four subjective segments in which individual characters relate their eye-witness accounts of a single event. These four personal accounts are themselves included in a narrative that contains a plot of its own, not necessarily connected to the central event described in each of the four segments. The complexity of the structure requires a shifting in mode for almost each sequence, which Kurosawa manages to handle without splitting his style into bits and pieces. Throughout, the camera style reflects the filmmaker''s unifying sensibility.

The inner story concerns three characters, Takehiro, a samurai, his wife, Masago, and Tajomaru, a bandit. Before the film begins each of the three characters has told his own version of the events to a magistrate conducting an investigation into the samurai''s death.

In the first version, Tajomaru the bandit explains to the magistrate how he cunningly tricked the samurai and his wife into following him into a remote part of the forest. After overcoming the samurai in a fight and binding him, Tajomaru attempts to take the woman by force. She determinedly and fiercely fights him off, gaining his admiration for her spirit; but suddenly finding the bandit desirable, she succumbs to him. Thus, Tajomaru''s story up to this point has made the bandit (1) exceedingly clever at his trade, (2) sophisticated enough to appreciate an extraordinary women even though she tries to kill him while defending herself, and (3) so masculinely attractive that he is capable of winning over this woman, not having to take her by force. Yet even at this, Tajomaru has not completed his description of his heroic escapades. The wife, he relates, insists that either the husband or the lover must die to salvage her honor. Tajomaru, understanding the validity of the suggestion, nobly cuts the rope from the samurai and engages him in a fantastic duel. Although earlier in this version he was depicted as being excessively cautious, perhaps even cowardly, Tajomaru performs like Zorro, and after a magnificent fight he slays the samurai. As he says to the magistrate, ''We crossed swords over twenty-three times. Think of that! No one had ever crossed over twenty with me before.'' He concludes by saying that the woman had run off during the fight, and he didn''t bother to look for her. Thus, Tajomaru admits to the killing, for as a notorious bandit he would undoubtedly be executed even if he were innocent of this particular crime. He has managed to gain our sympathy because his nature is inherently heroic and dignified.

The dominant tone of the second version, that of the wife, Masago, is pathos - which is, to her, an equivalent for masculine heroics, for she becomes the epitome of feminine sensitivity and human dignity, the helpless victim of an outrage. As she tells it, the bandit did rape her, then laughed and ran off into the woods; there was no sword fight nor any suggestion on her part that one of the two men must die. In fact, she runs weeping to her husband, still tied to the tree trunk, and throws herself first on the ground and then on him, pathetically imploring some kind remark from him. He remains silent, staring at her contemptuously. In his eyes she has been dishonored, even though she could do nothing to prevent the rape. When she cuts the ropes she offers him her dagger to kill her. He still remains absolutely unmovable, still implacably scornful of her. The filmscript at this point describes the woman as growing more desperate, and then in close-up, ''she moves steadily forward now; her world forever destroyed, she holds the dagger high, without seeming to be aware of it. The camera tracks with her in the direction of her husband until she suddenly lunges off screen.'' She claims to have fainted, probably not consciously aware of having killed him. She says that later she tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide and concludes her version by asking, ''What should a poor helpless woman like me do?''

The version of the dead samurai is told through a medium who conjures up his voice. (For the premise of the film, this conjuring must be accepted as a supernatural event; the story turns out as untrue as the other two versions, but not because of any interference with the materials on the part of the medium.) Takehiro, the samurai, claims that Tajomaru, after the rape, successfully consoled Masago, asking her to run off with him, as he really loved her. Takehiro describes his wife''s reaction - ''Never, in all of our life together, had I seen her more beautiful,'' - as she obviously returned the bandit''s love (the superb camerawork achieves the effect of making Masago look indeed more beautiful than she had elsewhere in the film). Masago agrees to go off with the bandit, but just before leaving she insists that Tajomaru kill her husband. From this point Takehiro shapes his story, as Tajomaru did his, to show his adversary as noble. In other words, Tajomaru has already described himself as the suffering husband shocked to discover his wife''s perfidy; now, he must elevate himself and his reaction to this perfidy by elevating the bandit. Tajomaru is made to share Takehiro''s shock at the revelation of Masago''s character; thus, Takehiro''s narrative makes the wife the villain and the bandit an upholder of the sort of code that Takehiro himself epitomizes. When Tajomaru throws the woman down and asks the husband whether he should kill her, the husband says that he almost forgave the bandit because of his assertion of the code of masculine honor. She runs away, and the bandit tries to catch her, returning hours later without having found her. Then Tajomaru, offering no explanation, cuts the samurai loose and walks off into the forest. Now Takehiro tells us that he heard someone crying, and in a close-up we see it is the isolated husband himself. Shortly thereafter, the husband commits suicide by plunging Masago''s dagger in his breast. After that, he remembers someone pulling the dagger from his breast as he died. Thus, the husband''s version, like the previous two versions, ends with the speaker''s claiming credit for the death of Takehiro - that death being the only ascertainable fact up to this point. And like the other two versions, the purpose of Takehiro''s account has been to show himself as a truly noble character, superior to the others.

The fourth version is told by the woodcutter, who hidden from view observed the episode without participating in it, although at the end it is apparent that he stole the dagger that was sticking in the ground (the other three versions agree that the dagger at one time was sticking in the ground, dropped by Masago during her encounter with Tajomaru; though the husband of course claimed it was eventually stolen from his breast). For having taken this valuable implement, a piece of evidence, the woodcutter feels incriminated to the degree that he did not tell his story to the police; instead he tells it at last only to the commoner and the priest. Kurosawa intends that this version stand for the truth, though many critics feel it is also a relative account.

RASHOMON is not a film about the relativity of truth, however; it is about the kinds of lies people will tell to protect their self-image, the most important possession a man believes he has. Normally, the final version of any controverted narrative represents the truth. For critics to doubt the fourth version, they must feel that the key to everything lies in the final remarks of the samurai that someone pulled out the dagger just as he died. First of all, if his remarks are true, then his story must be basically the truth, an impossibility here, for no narrative structure (literary or cinematic) could rest on a third version that contradicts two prior versions and is in turn completely contradicted by a following version. Some critics argue that the samurai''s final remarks are either a pointless lie or the truth. It is clear that his concluding lie is not pointless: he lies to cover the loophole in his suicide story, which no one could believe without his accounting for the weapon. He knows that objectively judged, he will appear to have been killed in a battle, the victor then removing the sword, which is what happened. The dagger later was stolen from the ground by the woodcutter, for it was a piece of valuable property that the poor man could not resist.

Rashomon not only won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951; it drew attention to a country previously overlooked in the cannon of world cinema. The film also elevated Kurosawa to the front rank of innovative directors and made an international star of Toshir¶ Mifune, whose performance displays an intensity that became a trademark of his collaborations with the director over the next ten years.

Using the now familiar dramatic device of a multi-perspective narrative, the film prowls through a dense forest uncovering the mystery behind a rape and murder. Seen from the point of view of the accused, the wife, the dead husband and a woodcutter, the murder creates a puzzle that explores themes that fascinated Kurosawa throughout his career. With each character''s version of the events, Kurosawa''s interest lies in exposing the characters'' dishonesty and egoism and challenging the notion of the existence of one universal truth.

Opening on the rain-soaked porch of a dilapidated house-cum-stage, the film''s narrators introduce each character''s stories. With each flashback the central protagonists are seen in a different light, from innocent victims to scheming manipulators. And an initially straightforward case of jealousy on the part of the bandit, becomes a more ambiguous case of the avarice of all concerned.

Along with The Drunken Angel (1948), Rashomon, saw a maturing in Kurosawa''s direction. The acclaimed tracking shot of the woodcutter''s walk in the forest displayed Kurosawa''s control of fluid camera movement, whilst the breakneck editing (the 86 minute film contains over 400 shots) showed his masterly control of pace. True, the film''s ending veers precariously towards sentimentality, or what Robin Wood has generously referred to as Kurosawa''s ''bitter humanism''. And the links between the past and present are occasionally crude. However, the film remains key amongst Kurosawa''s extensive body of work.

http://www.kamera.co.uk/reviews_extra/kurosawa.php

Film Frames - http://www.dvdbeaver.com/FILM/DVDCompare6/rashomon.htm

http://www.liketelevision.com/web1/movies/rashomon/ - Rashomon - Akira Kurosawa Classic (film scription)

After working in an extensive range of genres, Akira Kurosawa made his breakthrough film in 1950 with the technically perfect Rashomon. It won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival (Golden Lion), and first revealed the richness of Japanese cinema to the rest of the world. Heavily revered in the West, Kurosawa''s films have always been more popular there than in his homeland of Japan. His native critics often view his adaptations of Western authors and genres (ex. Shakespearean plays in Feudal Japanese settings) with apprehension. Kurosawa was best know for his utilization of the mis-en-scene - taking advantage of the full widescreen scope to isolate characters and introduce extraneous detail. His films ranged from samurai action to touching dramas. Kurosawa worshipped American director John Ford, signifying him as his primary influence as a filmmaker. He is quoted as saying "For me, film-making combines everything. That''s the reason I''ve made cinema my life''s work. In films, painting and literature, theatre and music come together. But a film is still a film."

The Films of Akira Kurosawa:

Madadayo (1993), Rhapsody in August (1991), Dreams (1990), Ran (1985), Kagemusha (1980), Dersu Uzala (1975), Dodesukaden (1970), Red Beard (1965), High and Low (1963), Yojimbo (1961), The Bad Sleep Well (1960), The Hidden Fortress (1958), Lower Depths (1957), Throne of Blood (1957), I Live in Fear (1955), Seven Samurai (1954), Ikiru (1952), The Idiot (1951), Rashaomon (1950), Scandal (1950), Stray Dog (1949), Drunken Angel (1948), No Regrets for My Youth (1946), Zoku Sugata Sanshiro (1945), The Men Who Tread On the Tiger''s Tail (1945), The Most Beautiful (1944)

Dersu Usala - http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%94%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%81%D1%83_%D0%A3%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B0

THE FILM IDEA by Stanley J Solomon (1972)

Kurosawa''s Classix Films Up Close

Kurosawa''s Films

Kurosawa''s Film List

IMBd