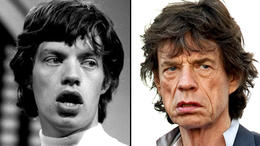

| Тридцать лет спустя...рок стар |

|

Syd Barrett 2003 |

The Wizard of Ozzfest: Osbourne |

Sebastian Kruger''s paint: Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ronnie Wood |

|

|

http://www.lacitybeat.com/article.php?id=5826&IssueNum=214#

Ozzy’s Black Reign

On the eve of Ozzfest, heavy metal’s Prince of Darkness reflects on his life

~ By STEVE APPLEFORD ~

Osbourne is back in the Bunker, and he is not alone. Not as he should be in this hideaway and inner sanctum, amid his crucifixes and Beatles memorabilia and the framed vampire-bat specimen by the toilet. It is the one place in the Osbourne manse where cameras are never allowed, not even in this year of our dark lord 2003, this latest anno diabolis domini of pop culture, the very moment that papa Ozzy and his family have ascended to become the supreme reality-TV stars on the planet. The cameras follow him everywhere now. That makes this den his escape pod, the place he goes to scratch his balls or blow his nose in peace and privacy. But not today. The Bunker has been invaded by a small crowd of strangers, by journalists and rock stars and publicists, gathering around him without warning. The room is filled with chatter, and the damn telephone won’t stop ringing as Osbourne’s eyes widen behind his purple shades. He has the look of a man in distress.

Sitting nearby is Marilyn Manson, a demon hard-rocker from a younger generation, pale and elegant in a dark gangster suit, a single contact lens giving his left eye the milky blue stare of a vulture. His lips are painted the color of coagulated blood, and he speaks cryptically of taking Ozzy’s teenage son Jack under his wing. Also in the room is Korn’s Jonathan Davis, another brooding, raging singer of alienation, obsession, and dementia. Just minutes ago they had all been in the Osbourne playroom for a press conference announcing plans for the year’s Ozzfest tour, smiling for the gathered music press as the family dogs scratched anxiously at the door from outside. The annual heavy metal fest is now one of the most successful events on the live music calendar, a monumental gathering of the metal tribes, of primal moshing and epic waves of noise. And its success predates Osbourne’s time as a beloved, fumbling TV dad, delivering him instead the way his true fans always want him: as a heavy metal ringmaster, incredibly loud and vaguely threatening, acting a little reckless and genuinely crazy, hopelessly fried but somehow engaged.

The press conference had been a good laugh, with moments that would be familiar to the MTV sitcom demographic. Ozzy mumbling wisecracks, daughter Kelly passing impatiently in and out of the room, and Jack joking about mama Sharon Osbourne having retired from the music management business: “Mom’s a TV star now.” And there were the inevitable questions about Black Sabbath, the band that launched Ozzy’s career and an entire movement of gloomy, heavy rockers for all the decades since. Osbourne and Sabbath had reunited a few times in recent years, but not this time. And one reporter wanted to know why. Sharon just smiled and glared at the reporter. “Cut the Black Sabbath shit, OK?” Laughs all around.

But, as Ozzy sits fitfully in the Bunker, enduring an interview he hadn’t expected, he speaks also of the cloud of despair he’s been under since his wife was diagnosed with colon cancer the year before. He could barely contain his fear enough to function on the road. For Ozzy, the arithmetic was simple: patient + cancer = death. That’s how his father went. Now Sharon was doomed, and, by extension, so was Ozzy. He would not survive without her. That year’s Ozzfest was the worst ever for him. Sharon was too ill to make it to a single show. “I honestly don’t know how I did it last year. I was on auto-pilot,” Osbourne says. “Every night when I went on stage I nearly passed out from fucking stress.” Today her cancer is in remission. She had her final dose of chemotherapy a few days before.

The phone rings again as he talks. He looks at it as the thing rings and rings, until he picks up the receiver and slams it back down. Then he yanks out the cord. The telephone, at least, is something he can control. But here in 2003, at the very height of his international fame and success, Ozzy Osbourne is not a happy man.

Now, in 2007, tour buses still slow to a crawl while passing the Osbourne house in Beverly Hills, which stands behind a high wooden fence and a plaque that reads: “Never mind the dog. Beware the owner.” Ozzy’s four years as star and domestic patriarch on The Osbournes are behind him. And the kids have grown up and out. Jack is now an extreme-sports fanatic in his fourth year as star of a reality-TV series in England, Adrenaline Junkie, where viewers watch him climb mountains and jump out of airplanes. At the moment, he’s in Mongolia. Kelly also appears regularly on British television. And Sharon now stars as a nurturing and sharp-tongued coach and critic on NBC’s America’s Got Talent! But Ozzy is back to just being a rocker, the grinning, howling Prince of Darkness at the center of the massive metal juggernaut that is Ozzfest.

The current tour is experimenting with a business plan that turns the festival into a kind of “Free-Fest,” with most tickets free to fans and distributed by a variety of paying sponsors. (Special VIP seats are also still available for the right price.) Among the tour stops will be a show at its usual SoCal hotspot, the Hyundai Pavilion in Devore on Saturday, July 21, with a lineup that includes such committed noisemakers as Lamb of God, Static-X, Hatebreed, and Nick Oliveri and the Mondo Generator, serenading the thousands of fans and bonfires, the bong merchants and booths selling T-shirts and spontaneous piercings and female breast painting.

The announcement of “Free-Fest” is still weeks away as Osbourne sits in his home studio in January. Things make sense here, in this elegant room painted with deep reds and blacks, a small disco ball hanging above the soundboard and scattered pictures of Keith Richards taped up for inspiration by guitarist Zakk Wylde. Osbourne and coproducer Kevin Churko are here, finishing his first album of new material in six years, and the sound is loud, confrontational. This is also the first album he has ever done completely sober, free of booze and drugs, even cigarettes. And he’s been arriving for work almost every day, sometimes as early as 10 a.m., actually recharged and thrilled to be creating music again.

“If you ever have inspiration, you can put down an idea,” Osbourne says with a grin. “The bad thing is, your wife can get ahold of you all the time for whatever she wants you to do. There’s no time limit. If you’re on a good roll, you can stay as long as you want.”

So far, Osbourne and Churko have finished nearly 11 songs, with two more in progress. And Ozzy sounds ready to keep working, at least until Sharon tells him to stop: “We’ve got another 24 to go. I said to Sharon, ‘Am I terminally ill and you’re not telling me?’”

The studio was built in the Osbourne guest house, where his oldest daughter, Aimee, once lived, safely out of camera range during The Osbournes years. He hasn’t named the room yet but is considering the possibilities, and may invite other artists to record here. “I was going to call it The Asylum to the Musically Insane. It’s what I always wanted.” He sits behind the soundboard as the songs-in-progress are played back, including “Not Going Away,” a grinding, intense rocker with metal riffs ominous and crisp from Wylde as Osbourne sings: “Don’t tell me I’m wrong … Only I know what goes on.”

There are also songs of war and absolute destruction. The new album is to be called Black Rain, a title taken from the grim phenomenon of contaminated black rainwater that fell on horrified survivors after the nuclear bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945. The song “Countdown’s Begun” is a modern metal track of churning guitars as Osbourne wails: “Don’t need a self-made prophet/Don’t need a holy war/Don’t need another leader/To even up the score.” He insists that he hasn’t set out to write another “War Pigs,” the classic Black Sabbath dirge inspired by an earlier generation’s unpopular war, but the imagery is unmistakable, a reflection of his daily doses of bad news on CNN, plus his own visits to military hospitals while on the road.

“All my life I’ve been worried about somebody dropping a fucking A-bomb on the house,” he says, but adds, “I don’t like getting too involved with that, because I don’t understand politics, and I don’t want to start pissing people off in the government because I don’t know what I’m talking about. And rock ’n’ roll should be about music. I shouldn’t start meddling in fucking politics. It’s only what I think, anyway.

“I try to mask it so you can think what you like,” he continues. “That’s what I loved about John Lennon’s lyrics and Paul McCartney’s together, fucking sweet and sour, cynical and nice. I’m so glad they were alive in my lifetime.”

On his right knuckle is a skull ring made of black and white diamonds. Things could be worse, and he smiles a gleaming white grin. Making this album has been far different from the old days, even at the height of his ’80s popularity, when he had to endure label execs coming by his recording sessions to pass judgment on the work: about how he needed a radio track, something upbeat, and nothing too dark. It was the usual meddling, as if Ozzy were just another new glam-rocker plucked from the Sunset Strip. “It was always a clusterfuck,” Sharon says later, “a case of too many cooks.” No more. There are a couple of softer ballads on Black Rain, including one inspired by his wife’s illness. But much of the rest is aimed at this generation’s war pigs in Washington, London, Iraq, Darfur, wherever there’s a TV camera. The man sounds angry, frustrated. The war is one reason for his dark mood. Here’s another: “Nobody plays my kind of music anymore. That’s why there’s the Ozzfest.”

onths later, Osbourne is back in the Bunker, drinking tea from a large porcelain cup. On the table is George Harrison’s final album. And around his neck hangs the same engraved crucifix he’s been wearing since 1973. He has others, including the treasured aluminum cross his father made for him in ’68, and the rough-edged crucifix made from World Trade Center wreckage for him by clean-up workers there.

At nearly 59, Ozzy Osbourne seems fit and energetic. He is no longer the chubby hedonist he was in the ’80s. Those days were at the beginning of his rise as a solo artist, a career move that was no guaranteed success when he involuntarily left Black Sabbath in 1979. With the help of guitarist Randy Rhoads and others, Osbourne became a multiplatinum artist, a wild-eyed MTV star. Much about that time is foggy now: the infamous scenes of him biting the heads off of small animals (doves, bats, etc.), passing out in strange hotels rooms, sometimes missing gigs, being banned for years from San Antonio after being caught drunkenly pissing on the front door of the Alamo. A fun guy, but there is a lot he does not remember, except for this: He should be dead.

“I was in a blackout from 1970 to about fucking two-and-a-half years ago,” he says now. And yet he can’t help but laugh when recounting some of the more insane moments. “I’ve got a bad rap from my crazy days. I’ve really turned around in the respect that I don’t eat my animals anymore.”

He does suffer from some short-term memory loss, mainly the result of a neck injury incurred after a 2003 off-road accident at his England estate and the medication that followed. The hand tremors from years of self-medication, which could sometimes be seen on The Osbournes, seem to be gone. And he mumbles as cheerfully, angrily, and incoherently as always. “I exercise a lot. I try and eat good food,” he says, a tattoo of an alien creature crawling up his right arm. “At the same time, I’m dieting because of my ego, and I don’t like being fat.”

If he seems like a happier person than he was at the press conference back in 2003, he dismisses such talk. The demons remain. “Me in a room by myself is bad company,” he says. “It’s just fucking bad, man. My head can go from anywhere to a nuclear holocaust. It’s just fucking nuts. I’m quite comfortable with the fact that I’m not fucking sane. I go to a psychiatrist. How many people do you know go to a psychiatrist?”

Earlier today, he was at an A.A. meeting, nervous as ever when speaking to the room. And when he returned home, he was met by Greta Van Susteren of Fox News, ready with a camera crew to talk about his nearly 40 years in music. They are friends. It was she who secured the Osbournes invitations to the 2002 White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner, where President Bush joked from the podium: “Ozzy, Mom loves your stuff.”

Ask Ozzy about “Free-Fest,” and this is what he’ll say: “I don’t know what the fuck that’s all about.” He doesn’t.

These things are the domain of Mrs. Osbourne, who has been his manager since his exit from Sabbath, who helped the Prince of Darkness chart his unlikely survival through the decades. And she conceived of Ozzfest in 1996 as a response to the various rock festivals (Lollapalooza, H.O.R.D.E., Lilith Fair, etc.) that would never invite the likes of Ozzy to perform.

Ozzfest would focus on loudness, heaviness, darkness, and it would outlast virtually all competitors. (Only the Warped Tour, catering to generations of punk bands and fans, has been around as long.) And Sharon Osbourne insists that this year’s “Free-Fest” will not be a total free-for-all, with the doors opened wide to whoever chooses to squeeze in. This will not be Altamont.

She’s also quick to point out that this is a one-time experiment that will not be repeated. Free tickets have been distributed to lucky fans, and there has been the inevitable profiteering by scalpers. But Sharon says “Free-Fest” was a needed break from the first 10 years of Ozzfest, which had slowly become a victim of its own success. The major acts that joined Ozzy at the top of the bill were demanding more and more money, and ticket prices were destined to go up ever higher as a result.

“This festival initially was to keep this genre of music going,” Sharon says. “We needed a festival for this genre of music. And when we started, there was no other festival for this genre. We paved the way for other festivals. We’ve given young bands an opportunity to play in front of large audiences. We’ve done extremely well out of it, financially, reputation-wise. We’ve gained a lot from it, too. But it’s like a two-headed monster. You can’t earn enough to feed it. It’s got too big.”

This year, bands are not being paid by the Osbournes, but are being supported by their labels or other sponsors. That means the lineup perhaps isn’t as stellar as some recent years (System of a Down in 2006; Sabbath, Slayer, and the reunited Judas Priest in 2004), but the scene of metal multitudes baking beneath the sun will likely remain unchanged for 25 days and nights on the road