| The U.K. in L.A. |

|

Jacqueline Bissett |

Julian Sands |

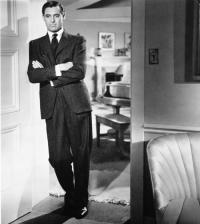

Theyíve come a long way, baby: Cary Grant and fellow British expats... (Courtesy LACMA) |

|

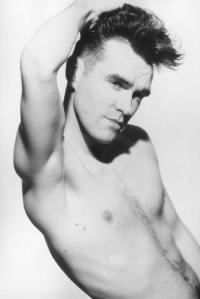

Latin lover: Morrisseyís pompadour and melancholic ennui drive the cholos wild |

Ian Whitcomb (Courtesy KPCC) |

Bob Hope |

The U.K. in L.A.

or, How to be Cary Grant

By DAVID EHRENSTEIN

The ocean appears suddenly. You turn another hairpin bend and the land falls away and there is a long high view down Santa Monica Canyon to the pale Pacific waters. A clear day is not often. Sky and air are hazed now, diffusing the sun and dredging the ocean of its rightful blue. The Pacific is a sad blue-grey, and nearly always looks cold.

Each time I drive down here it feels like the end of the world. The geographical end. Shabby and uncared for, buildings lie around like nomadsí tents in the desert. There is nowhere further to go, those pale waters stretch away to the blurred horizons and stretch away beyond it. There is no more land ever.

óGavin Lambert

Those deliciously foreboding words were written by Lambert in The Slide Area, the episodic novel he penned in 1959, just a few years after arriving in Los Angeles to write screenplays for his erstwhile lover, film director Nicholas Ray. And while such sentiments would seem to suggest Lambert was about to make a quick exit, the British novelist (Inside Daisy Clover), critic (On Cukor), screenwriter (Sons and Lovers) and film historian (Norma Shearer) stayed on in L.A. until his death last year at the age of 80.

I first came upon The Slide Area in the early 1960s, when I was in high school. Years later, the deathless clichť ďNever meet your heroesĒ proved wrong when the man most responsible for my decision to become a writer proved generous with his time and erudition as I wrote Open Secret: Gay Hollywood 1928Ė2000. I soon learned he was this way with everyone. When the film department of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art kicked off this springís retrospective tribute to Lambert with a screening of Another Sky, the only film Lambert both wrote and directed, the gathering drew such equally fabulous British expats as Barbara Steele, Jacqueline Bisset, Michael York and Julian Sands, all of whom, like Lambert, have made L.A. their second home.

As anyone even casually familiar with Los Angeles history knows, the town has long been a haven and inspiration for Englishmen (and women), from the writers Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood to others of lesser fame but no less interest. The singer/songwriter/pop-music historian Ian Whitcomb, who first came here to produce a rock & roll album for the ineffable Mae West, even made a documentary about the U.K./L.A. phenomenon, L.A. My Hometown (1977), dealing ďwith everyone who wasnít Christopher Isherwood or David HockneyĒ (like Playboy photographer Suze Randall) in a brisk and cheeky style

Isherwood has since passed on, but Hockney is as omnipresent as ever, evidence the recent LACMA retrospective of his portraits ó a reminder of how central the city has been to Hockneyís work, and how that work has come to embody the image of L.A. worldwide.

ďPeople in New York said youíre mad for going there if you donít know anybody and you canít drive,Ē Hockney writes in his autobiography My Early Years, recounting how the city lured him away from coldest, wettest England to a world of bright sunshine, blazing color and beautiful naked men.

ďThey said, ĎAt least get to San Francisco if you want to go West,í Ē Hockney continues. ďAnd I said, ĎNo, no, itís Los Angeles I want to go to. I had read John Rechyís City of Night, which I thought was a marvelous picture of a certain kind of life in America. It was one of the first novels to cover that kind of sleazy, sexy hot nightlife in Pershing Square. I looked at the map and saw that Wilshire Boulevard, which begins by the sea in Santa Monica, goes all the way to Pershing Square; all you have to do is stay on that boulevard. But of course, itís about eighteen miles, which I didnít realize. I started cycling. I got to Pershing Square and it was deserted; about nine in the evening, just got dark, not a soul there.Ē

But Hockney returned at a more auspicious hour to visit the studios of Bob Mizer, whose Athletic Model Guild magazines (softcore gay erotica considered daring in the í60s, but literally on par with todayís Abercrombie & Fitch catalog) had inspired such Hockney works as Domestic Scene, Beverly Hills. However, as art historian Cecile M. Whiting has noted, ďItís Beverly Hills, not downtown L.A. Hockney has the boys move up a class.Ē In other words, Hockney ďrescuedĒ the street hustlers who were Mizerís principal subjects and turned them into ďupright,Ē upper-middle-class gay citizens. Or at least a better class of hustler. Itís just that promise of class mobility that has always attracted the English to western shores, even as they find traces of home in their new land.

ďThere was a program I saw recently on Hockneyís newest work,Ē says Barbara Steele, the raven-haired British beauty who first gained fame in Italy in Mario Bavaís Black Sunday (playing the most imposing vampire since Christopher Lee) and Felliniís 8½ (as a delectable philosophy student) before coming to L.A. under contract to 20th Century Fox. ďHis latest paintings have the English light. Theyíre very muted, and donít have those wild Matisse colors his L.A. paintings had. Heís really gone back now. To look at him, heís an English country gentleman in tweeds with a waistcoat and an English hat. Itís just fantastic how people go back to their roots. And you know, Wash comes from the same area of England as Hockney.Ē

One of the more recent émigrés, Wash Westmoreland has quite a way to go before turning into a Town & Country squire. Quinceañera, the Sundance-awarded, critically acclaimed cinematic slice of Echo Park Latino life he co-created with his American work-and-life partner, Richard Glatzer, has its roots in the British lower-class ďkitchen sinkĒ realism of the 1960s. But that doesnít mean Westmoreland is pining for home.

ďI never thought of myself as staying here,Ē Westmoreland says. ďMy report back to my friends in England was that L.A. is a city without a soul. You know the feeling that you get in a great city like London or New York? Do you get that in L.A.? But when Rich and I moved to Echo Park, I finally felt this was a place with a soul where I could live. Itís interesting that so many people think of coming to L.A. as coming to Hollywood, whereas for me the real interest lies everywhere else in the city. I guess Iím an outsider by two degrees ó by being white and by being English. So when Latino people say to me that Quinceañera is true, thatís the greatest compliment I could ever have.Ē

British pop star Morrissey encountered a similar phenomenon during his own nine-year L.A. residency, when ďtributeĒ bands began springing up in the Latino community (as documented by William E. Jones in his 2004 film Is It Really So Strange?), having discovered in the lower-class British dandy a kindred spirit. Morrisseyís ultraemotional singing style, coupled with his look ó particularly his pompadour hairdo ó is very much in keeping with Mexican pop singing. But Mexican pop stars donít have the special edge of melancholy regret and worldly-wise ennui that drives his L.A. Latino fan base wild. As Jonesí film notes, tough-as-nails cholos have been known to break down sobbing at ďMozĒ concerts.

ďAt first, being here was strange and isolating and completely spacy as far as I was concerned,Ē recalls actress Jacqueline Bisset of her mid-í60s introduction to L.A., when she was chosen to be part of Foxís new-talent program. ďI was very much on my own. There wasnít a soul I could call. I was living in the Beverly Hillcrest Hotel on Pico, which is now something else. There was nothing around there. I arrived at midnight. The person who had been warning me about the perils of Los Angeles promptly tried to seduce me.Ē

A look of dark disgust briefly flashes across Bissetís comely features. She has no interest in identifying this soi-disant masher, but she has a lot to say about the L.A. she first encountered in that hotel.

ďMy room was orange. Everything was orange. Iíd never seen a king-size bed. The cover on it was orange. The drapes were thick and closed. And I had a little fridge in my bathroom. That was the coolest thing. I couldnít find a market anywhere. I didnít know where to go. I was on the moon. When I turned the radio on, I heard people talking about thefts and murder for very small sums of money. So I thought, ĎI think Iíd better stay in the room.í Ē

Still, there was an upside.

ďI thoroughly enjoyed the new-talent program at Fox,Ē says Bisset. ďI would see people like Henry Fonda and Raquel Welch wandering around the dining room. I must say Henry Fonda was a smashing-looking man. He gave it class. It was the end of the studio system. I said Ďnoí to a contract, but I had a 10-picture deal. I didnít want to be owned by anybody. If anybody tried anything dodgy, Iíd just go home to England and be fine. ĎYouíre not touching my eyebrows, youíre not touching my hair color,í etc. It was all very defensive, but people accepted it.Ē

Of the cityís British expat community, Bisset says sheís not quite connected to it: ďI think if Iíd had an English boyfriend, I would have been part of a circle here. But for many years, when Michael Sarrazin and I were a couple, I lived a very closed kind of life. I remember articles questioning why I wanted to Ďlive in siní when there was cash to be had. I remember girls asking me, ĎWhy donít you get married and get something out of it?í That was a very strong attitude here ó getting some money off the marriage contract. It shocked me a lot.Ē

Resembling nothing so much as a French farmhouse (ďMy cleaning lady said thereís nothing American in here except the light bulbsĒ), Bissetís Laurel Canyon residence was previously owned by Vincent Price, an Englishman who made so successful a transition to America that few think of him as being English at all. But the absolute ďtransatlanticĒ champion is, of course, Cary Grant, a lower-class Englishman who, thanks to Hollywood, became the embodiment of class and sophistication for the entire world.

ďCary Grant!Ē Bisset exclaims. ďOh, he was so tanned ó he was a knockout. The English look of him was great, but he had very much a royal quality. It was something of an upper-class accent with cockney cadences. He wouldnít fit easily into England. If you put him into England, where would he fit? But then again, he could go anywhere he wanted.Ē

And that he did.

The mention of Grantís name also brings a smile to the lips of actor Michael York, who first caught moviegoersí eyes as a sprightly Oxford student in Joseph Loseyís Accident, achieved movie immortality as Christopher Isherwoodís quasi surrogate in Cabaret and more recently has popped up as Basil Exposition in the Austin Powers series.

ďCary was a friend of mine,Ē says York. ďI forget when I met him. He used to love going to the races. I loved going with him. Not so much for Ďthe sport of kings,í but to be with Cary Grant. The week he died, we were at the track, and David Hockney was there, and he [Grant] was picking our brains for jokes.

ďFor a time, before I settled here, I was a resident of Monaco, and I got to know Princess Grace. At one of the first lunches I went to at the palace, there was Cary Grant. He came in, and as he went to say hello to my wife, Pat, he tripped and fell into her arms. Without missing a beat, he looked up and said, ĎThereís nowhere else Iíd rather be.í Ē

For her part, Pat York recalls a meeting with another Anglo-American, whose status as such is rarely acknowledged: Bob Hope. ďI was seated next to him at dinner one night, and he told me this incredible story. He had gone back to visit his hometown, Elton. He saw a man walking down the road, and he said, ĎIím Bob Hope, and I was born here and lived here, you know,í and the man said, ĎI know,í and walked on. So he went to the house and knocked on the door, and a woman answered. He said, ĎIím Bob Hope, and I was born in this house,í and she said, ĎYes, I know,í and slammed the door in his face.Ē

Michael York has felt that same chill. ďAfter a time, your accent inevitably picks up overtones,Ē he says. ďI remember being accosted by a London cabdriver and asked, ĎWhy are you speaking American?í Ē

Now 95 years young, director Ronald Neame got into the business by a circuitous route. ďI came over in 1944,Ē he recalls. ďI was sent over here by [British movie mogul] J. Arthur Rank ó the man with the gong ó who was a very important gentleman, because he owned somewhere around 880 theaters. He asked me to visit all the studios and assess what we need in England to bring us up to date with Hollywood when the war was over, which we knew was going to happen

ďThere was no question of flying over back then,Ē Neame continues. ďI came on the Queen Elizabeth. It had half ordinary passengers, 800 wounded American soldiers on their way home and 800 German POWs who were on their way to prison camps in America. The reason we had the 800 POWs was, the feeling was Hitler wouldnít sink us if we had German prisoners onboard. We zigzagged across the Atlantic. Then I arrived in New York, this magical city. I cannot tell you how extraordinary it was to come out of war-torn Britain, with blackouts and shortages of everything. It was pure magic.Ē

But Neame was on his way to L.A., where he found any number of fellow countrymen (ďWe had a cricket team. There were a lot of people who played croquet. Ronald Coleman, I rememberĒ), along with American equipment, much needed after the war. ďWe were a great little group of filmmakers, and we had a wonderful eight or 10 years,Ē he says of the postwar period, during which (with the help of that U.S. equipment) he produced such David Lean classics as Great Expectations and Brief Encounter and photographed Leanís film of Noel Cowardís Blithe Spirit as well as Powell and Pressburgerís One of Our Aircraft Is Missing. ďWe thought it would go on forever. But then [the industry] collapsed. So then United Artists adopted me. The Horseís Mouth, Scrooge, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie ó they were all British pictures, but the finance came from America.Ē

And so Neame found himself, purely out of professional necessity at first, buying a home in L.A., which he still lives in today.

ď[Producer] Harry Saltzman came up to see me here about making a film, which was never made, and he said, ĎWhat a lovely little place youíve got here. Exactly the kind of place I would like,íĒ Neame says. ďI told him I wanted to sell it. He said, ĎWell, look, I want to give you some advice: A few weeks ago, I went home and my wife was writing a letter. She has cancer. I said, ďWho are you writing to?Ē And she said, ďIím writing to you.Ē ďWhy?Ē ďWell, when I die, I want you to promise me that you wonít sell this house for one year, because after that year, you may find that you want to keep it.Ē Thatís my advic

These days, Steeleís name can be found everywhere from the ďthank youĒ list at the end of the indie film The Fluffer to the executive-producer credits of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Itís no surprise, as Steele embodies what drives so many British souls to live here: an instinctive antipathy to the social status quo, a restless intellectual energy, and a desire to explore new things, new ways and new people. And for Steele, nobody embodied that ideal better than...

ďCary Grant. He was the best-pressed suit you ever saw. I have several letters from him, and the signature is divine because itís one of those iconic signatures like Picasso had or the Coca-Cola logo: ĎCary!í I met him a thousand years ago in London. There was an article about me in Life magazine because of a movie I was in for about 30 seconds. He wanted to put me in a film with him. He put a bid in on my contract. It was really strange because at the time, I had never seen a Cary Grant movie. My mother was thrilled. He was fabulous. He sent his car around ó this cream-and-brown Rolls from the Savoy came to my parentsí house in London, with this ravishing-looking chauffeur. Iíd get in and spend the day with Cary. He took me everywhere. I met everyone with him. Playing charades with Tennessee Williams. We just had this fantastic time.

ďNo, I didnít have an affair with Cary Grant,Ē Steele says, answering a question I would never have dared to ask. ďBut he was the movie star. I remember having dinner with him at the Savoy and somebody trotting over to him and saying, ĎSo sorry, Mr. Grant,í and having an autograph book all ready, and he said, ĎIím sorry too.í Ē

Despite her fond memories of London, Steele says sheíd never move back. ďEurope gets further away every year,Ē she muses. ďWe [Brits] have this rapturous life here, which is like an insane drug, an incredible mistress. But itís so much better here now than when I first came. Itís much more global. And itís timeless. Thereís not a deep sense of time. It just sort of glides along and you donít have a sense of urgency. Maybe thatís why the most difficult journey you can make is from here to the airport.

ďI donít know what it is about this town,Ē she says, with a deep, rich chuckle. ďWeíre all trapped in its golden arms!Ē